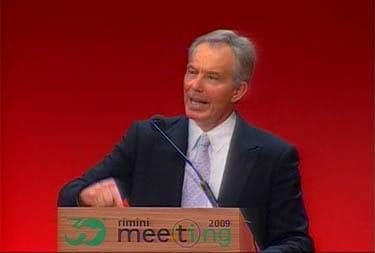

It is a privilege to address the famous Rimini Meeting. It is an honour to be associated with “Comunione e Liberazione.” It is a pleasure always to be in Italy. It is here in this country that I have spent many happy times; and where 30 years ago, almost to the day, I proposed to my wife and three decades and four children later, I at least am still pleased to recall the memory.

I am also, as you know, a very new entrant to the Catholic Church. I am therefore humble about addressing such an august gathering of so many eminent people. But I thank you for making me so welcome. Ever since I began preparations to become a Catholic I felt I was coming home; and this is now where my heart is, where I know I belong.

I have just returned from China. I visit China often. It has endless fascination for me as I watch it develop, not just economically, but politically and culturally. A feature of my visit was to discuss climate change with the Chinese leadership, and issue on which, contrary to much Western suspicion, China is showing real determination and commitment to put its economy on a low carbon path. I spoke at a meeting in one of the poorest provinces in a city called Guiyang and witnessed their challenge: to bring their people out of acute poverty by economic growth, at the same time as trying to make such growth sustainable through using clean energy sources like solar power.

But, as ever, what I came away with was more than I expected. I also discussed healthcare reform and how China seeks to develop its own welfare state. They are grappling precisely with the relationship between the person, the state and the community and coming up with some interesting and radical solutions that might surprise us. They are studying what we have done, what we have got right and what we have got wrong. They are acutely aware of the balance between the state and the need for individual responsibility, between universal provision and competition. They will do it, of course, in a Chinese way, but the dilemmas and choices in policy we would recognise instantly.

However, there was something else that excited me. I know relations between China and the Church remain difficult for obvious reasons, though I hope in time these can be resolved. But listening carefully to the speeches on the environment, hearing the way they describe the relationship between the individual and government, society and the state, I was struck at how, increasingly, China is developing a narrative about its future that draw heavily on its culture, on its civilisation now thousands of years old, and on its Faith traditions and philosophy: Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism. Several people I met talked openly of their Faith and yes, some were Christians, part of a growing Christian movement.

China, a country both ancient and new, the People’s Republic celebrating its 60th anniversary this year, is expressing in its own fashion, the limits and limitations of seeing society simply as a technocratic or legal bargain between individual and state.

This should give us pause for reflection; and hope too.

As Prime Minister of the UK for 10 years, but also as Leader of the Labour Party for 13, during which time I reformed its constitution precisely around the relationship between the individual and the state, I learnt many things. I began hoping to please all of the people all of the time; and ended wondering if I was pleasing any of the people any of the time. But that’s another story.

I learnt that the state is best when enabling and empowering; when it is seeking to supplement the individual’s efforts and creativity and not substitute for them; when rather than trying to control our lives, it seeks to widen our opportunities to control our own. We need the state to help organise public services upon which, particularly the poorest people depend.

But we don’t need the state always to run them and we need such services to be accountable to the people, not the other way round.

I trace the development of 20th century politics and ideology in this way. In the early 20th century, the Industrial Revolution had transformed the world of work, but many were without protection, the fruits of their labour taken from them. So in all our nations, the welfare state began – systems of national insurance, public education and healthcare.

But, in time, as people grew more prosperous and their taxes funded the services provided, so they began to look for quality, choice, systems more responsive to their individual needs.

Thus began, certainly in the UK, but also elsewhere, the drive for reform, for curbing the power of the state, indeed the power of all collectivist institutions like trade unions.

Today we seek a balance between the equity of state provision; and the individual choice more usually associated with the private sector. I developed this, in the UK, into what I called a Third Way between an over mighty state and an untrammelled market. This was the philosophy behind our reforms in the National Health Service, education, pensions and welfare.

We also strongly developed the community or voluntary sector. As Professor Vittadini knows – and I commend greatly the work of Fondazione per la Sussidiareta – there is not just room, but a growing space today for organisations of civic society to step forward and do things that neither market nor state can do.

Many such activities derive from people of Faith; many from our Church. I think of the work it does in tending the sick, comforting the distressed, befriending those without friends on our streets, in our cities but also in remote parts of Africa where without our Church, driven by our Faith, many would be without hope, without love, even without life itself. I only wish these good works received as much publicity that any failings receive.

But such work has a more profound significance and this I also learnt in my years running the government of a major country. I learnt over time that person and state, even bolstered by community is insufficient. That a society to be truly harmonious, to be complete, also requires a place for Faith.

The limits to individualism are in one sense, plain. We only need to contemplate the financial crisis to understand that the pursuit of maximum short-term profit, without proper regard to the communal good, is a mistake and leads to neither profit nor good. Yet, at a deeper level, the case against a purely individualistic or materialistic philosophy has to be made. Young people today have access to technology, to opportunity, to experiences good and bad on a scale my generation never knew and my father’s generation would find fantastical, like something out of science fiction.

The danger is clear: that pursuit of pleasure becomes an end in itself. It is here that Faith can step in, can show us a proper sense of duty to others, responsibility for the world around us, can lead us to, as the Holy Father calls it “Caritas in Veritate.”

After the experience of fascism, Soviet Communism or viewing life in North Korea or the Cultural Revolution in China, it is easier for us to grasp the dangers of a too-powerful state.

But I would argue that even the concept of community has its limitations. We use the word in two senses: one to distinguish it from government, to emphasise civic society if you like; the other sense is just to describe the general community of public opinion. In politics, of course, especially in a democracy, “the people” are the boss; public opinion is to be courted and if not surrendered to, as least managed.

It is here that Faith enlarges and enriches the idea of community. The recent Papal Encyclical is a remarkable document in many respects. It repays reading and re-reading. But one strand throughout it, is a strong rejoinder to the notion of relativism, to the description of the human condition in society as just some amoral negotiation or set of compromises with modernity; or even just obedience to the majority opinion. Not that it is anti-technology or anti-modern; or indeed anti-democratic.

But it widens and deepens the relationship between individuals and the community in which they live. It puts God’s Truth at the centre of it. In one passage, it describes humanism devoid of Faith as “inhuman humanism”: “Without God, man neither knows which way to go, nor even understands who he is.”

I think this even more relevant today for this reason. We live in the era of globalisation. Our countries, our communities are increasingly melting pots of different Faiths, races, cultures, ethnic backgrounds. The internet, mass communication, travel, migration: the world is coming together. One danger is we lose our identity.

But there is another: that we fail to understand that a global community, just like a country, if it is not to be dominated merely by the most powerful or driven by the short-term, needs a strong sense of shared purpose, a countervailing force generated by the pursuit of the Common Good.

There is no going back to old insularities. We are indeed today interdependent. Take any challenge – the financial crisis, climate change, terrorism. None of these can be solved by any one nation alone, not even America. We have no alternative but to seek alliances. But to what ends and motivated by which values?

Again, to quote the Pope: “Globalisation makes us neighbours but it does not make us brothers.”

How will we deal with the world’s scarce resources? Who will speak up for the poor, the dispossessed, the refugee, the migrant? How will we bring understanding in place of ignorance and tolerance in place of fear?

It is into this space that the world of Faith and of course the Catholic Church, the universal Church – itself the model of a global institution – must step.

Political leaders on their own – I tell you very frankly – cannot do this. Not because they are bad people; but because the context and constraints within which they operate make it hard for them to do so. But they can be helped. I remember when we put climate change and global poverty on the G8 agenda in Gleneagles in 2005, there was considerable disquiet amongst the politicians, worried about the demands made on them. But their burden was lightened by the Christian Church giving such solid and clear support.

In seeking this path of Truth, lit by God’s Love and paved by God’s Grace, the Church can be the insistent spiritual voice that makes globalisation our servant not our master.

It has another purpose too. A natural part of such a mission, is to work with those of other Faiths, in our countries and beyond. In my foundation – dedicated to respect and understanding between the religious Faiths – I always say clearly: I am and remain a Christian, seeking salvation thru our Lord, Jesus Christ. Globalisation may push people of different Faiths together. But it does not mean we all become of one, lowest common denominator, belief. We are together but retain our distinctive Faith. We respect each other. We are not the same as each other.

However, we work together. So my foundation has a schools programme now operating in around 20 countries in three continents that as part of student’s religious education uses the internet to let them talk to each other across the Faith divide. So last month I joined a session between a school in Delhi, one Bolton in England and one in Palestine.

We also have a programme to link up the Faiths in the fight against malaria, which kills one million people, mainly children each year in Africa. Many communities in Africa do not have a health clinic. But every community has a Church or Mosque. We are helping establish interFaith organisations – starting with that of Nigeria led by the Archbishop of Abuja and the Sultan of Sokoto, the leader of the Muslim community. They will, with help from the World Bank, mobilise their Faith communities, train health workers, provide and bring the medicines and bed nets that can save lives. I could also point to examples in Rwanda, Mozambique and Mali.

Here is the point. Too often religion is seen as a source of conflict and division. It is this manifestation that allows the aggressive secularism in part of the West to gain traction. Show instead how Faith is standing up for justice, for solidarity across peoples and nations, and how it is doing so with those of other Faiths and we show the true face of God’s love, mercy and compassion.

This is surely the role of Faith in modern times. To do what it alone can do. To achieve what neither a person, nor a state, nor a community, on their own or even together, can achieve. To represent God’s Truth, not limited by human frailty, or by the interests of the state or by the transient mores of a community, however well intentioned; but to let that Truth bestow on us humility, love of neighbour, and the true knowledge that indeed passes all understanding.

This is Faith, not as superstition, not as an insurance against life’s pitfalls, but Faith as the salvation of the human condition.

Faith not as magic, not as an escape from life’s complexities, but Faith as purpose in life. Faith, not as a mystery we seek to solve; but Faith as a mystery which expresses the limitations of the human mind.

Faith and Reason are in alliance, not opposition.

They support each other; embrace each other; strengthen each other. They are not in a struggle for supremacy. Together they are supreme.

That is why the voice of the Church should be heard. That is why it should speak confidently, clearly and openly. Because within any nation and beyond it, in the community of nations, the voice of Faith needs to be and must be heard,

It is our mission for the 21st century. For modern times. For the future. Science, technology, all the advances of humankind, do not make its voice less important. They make it more so.

So, even with all the diffidence of someone newly into full communion with the Catholic Church, I say: be strong and of good courage. The best days of our Faith, with God’s will, lie ahead of us.

Thank you.